Interview by Charlie Connell and Edmund Sullivan

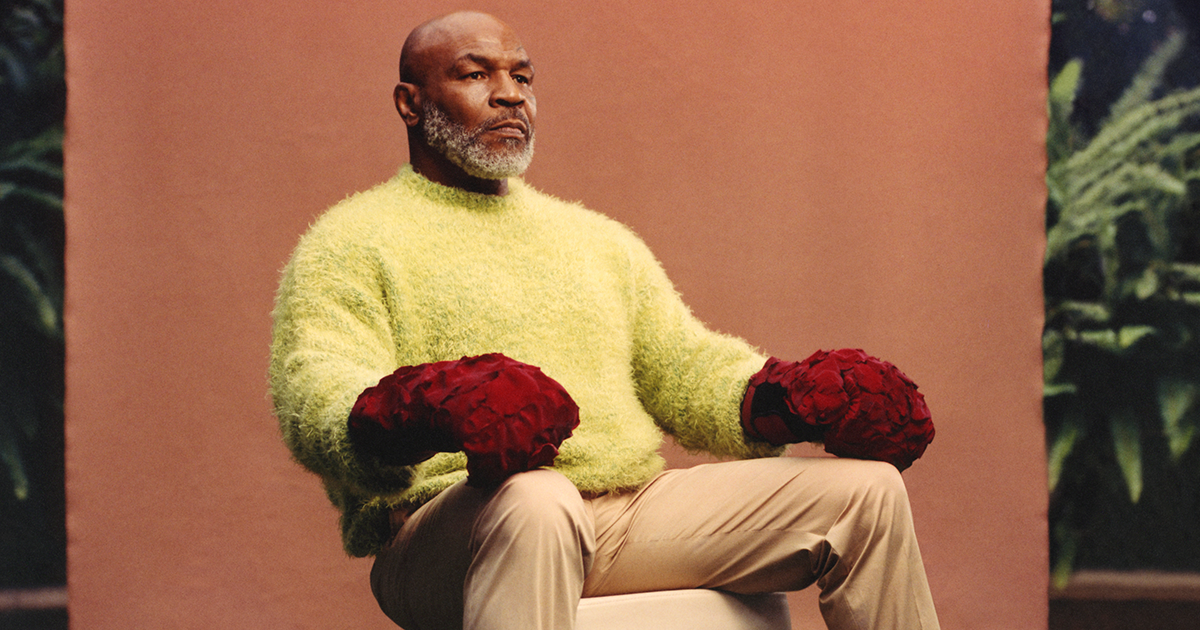

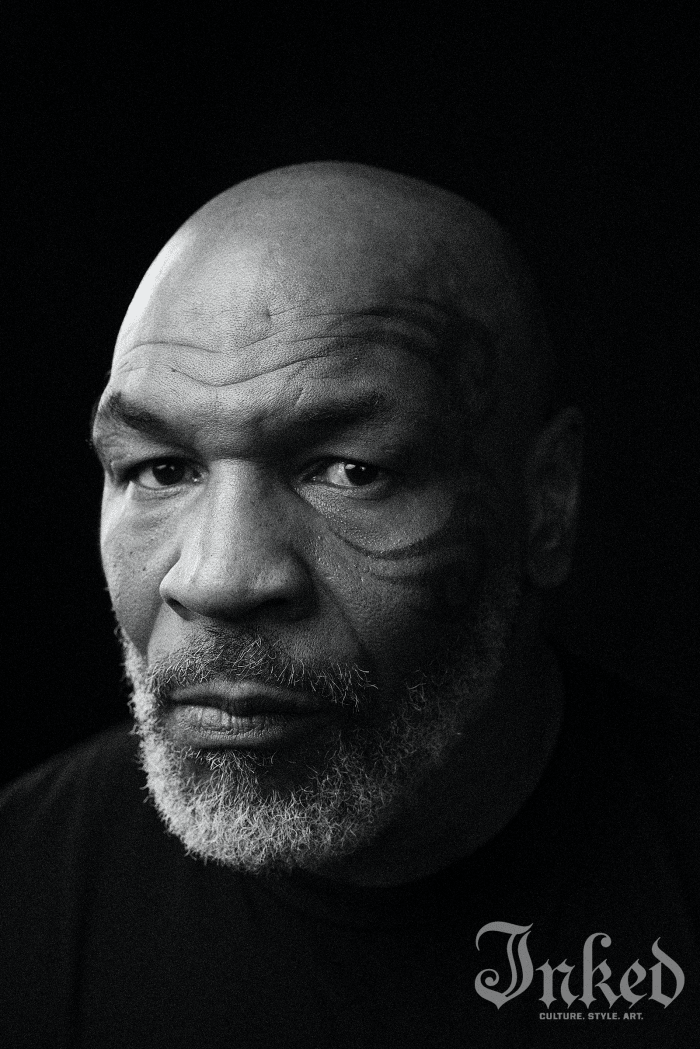

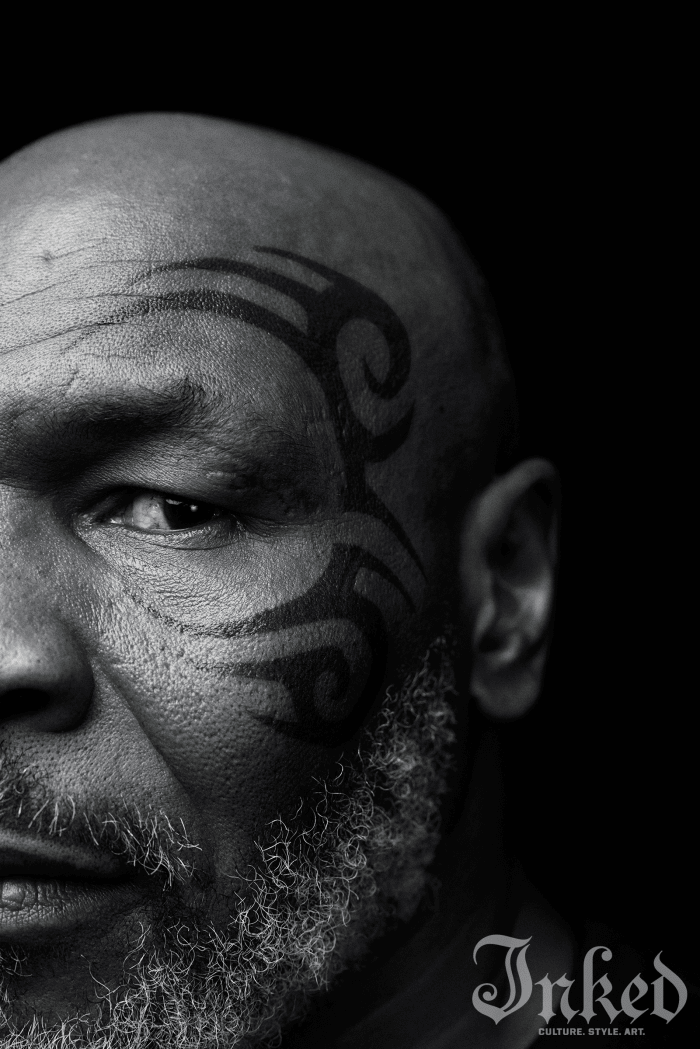

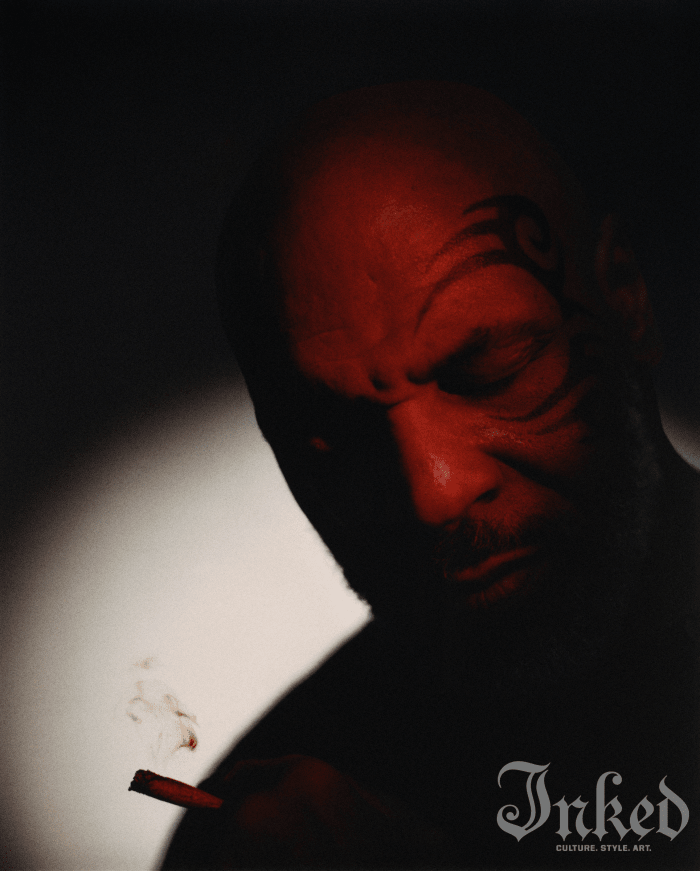

Photos by Mark Clennon

Two hours before my interview with Mike Tyson I’m scrambling to figure out how to structure the conversation. The man has lived so many different lives, each of them fascinating in their own right, that it’s nearly impossible to figure out a plan of attack. In a way I feel like so many boxers must have felt before getting into the ring with the legend—confident in my abilities but in full knowledge that this interview is going to go wherever Tyson wants it to go, regardless of the blueprint.

The Inked crew is ushered into his house and takes a seat in the family room. Tyson’s dog Mars, a big fluffy beast who leans hard into your leg as he accepts some pets, ambles around the room as we wait. A whiff of cannabis comes in from another room as we overhear the immediately recognizable voice approaching.

The former heavyweight champion ambles into the room. His beard has gone white and he moves with some trepidation, not uncommon for a man in his fifties. It’s as we shake hands—his massive right envelops mine—that the sheer power that made him a household name is evident. And as I introduce myself it becomes clear how this interview should unfold.

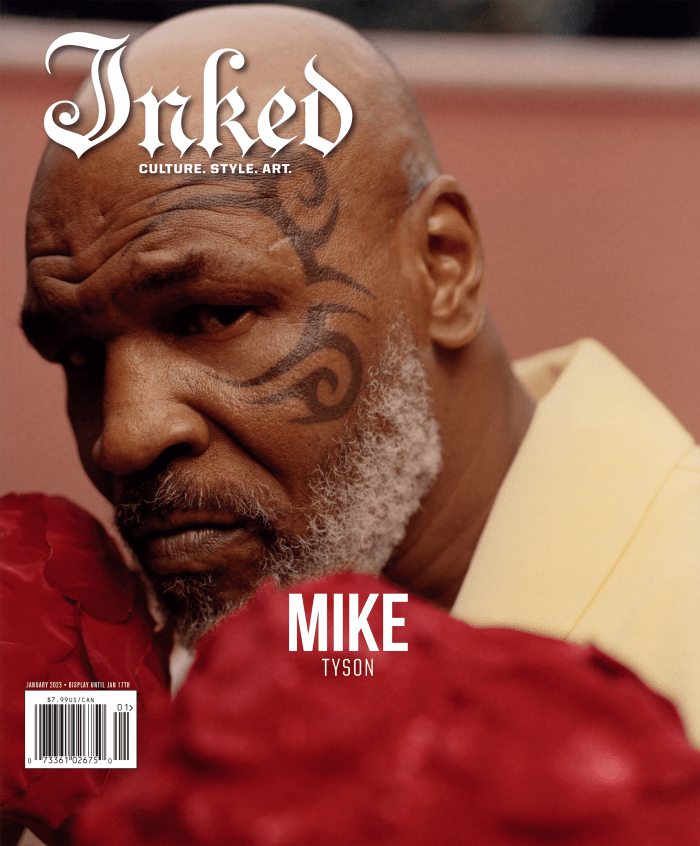

“What is it like to have the most famous tattoo on the planet?” I ask, referring to the tattoo framing his left eye.

“I think it’s pretty cool…” Tyson says as he contemplates whether or not the answer is accurate. “Listen, my family and my friends started crying [when they saw it]. ‘What did you do to your fucking face?’ Now look [laughs]. Without knowing it, this was the best thing that ever happened to me. I had a really menacing attitude back then, I was pretty rambunctious back then, so I went and did it.”

The tattoo was inked mere days before Tyson got in the ring to fight Clifford Etienne. Calling the fight forgettable is probably too kind—Etienne was knocked out in under a minute in what would end up being the final victory of Tyson’s professional career. The tattoo, on the other hand, was instantly iconic.

If Tyson had gotten a tattoo of what he had originally imagined there is no doubt that it too would have become the subject of lore, but with a completely different tone. “I went to [the tattoo artist], some little white guy, and said, ‘Why don’t you put hearts on my face?” he recalls. “He’s like, ‘I’m not putting that on your face.’”

The artist, S. Victor Whitmill, came up with a design that suited Tyson far better than a bunch of hearts would have. It was a foregone conclusion that he’d be leaving the shop with a tattoo, but it was through some quick thinking that he walked out with a piece destined for infamy. And despite those tears from his family and the scrutiny in the media, Tyson never wavered in his conviction to get the piece.

“When I do something, it’s because I want to do it,” Tyson says. “It’s my face, this is what I always wanted people to know. I know people care about me, but they have to know this is my life. It may not be the right life, but it’s my life to live the way I want to live it. That’s who I am.”

This opened up an interesting line of questioning. In his retirement, Tyson has done a lot of work to let people into his inner world and show them who he really is as a person. As we listened to the soft-spoken middle-aged version of Tyson discuss Nietzche and Bible scripture, the level of ferocity that once defined him seems unfathomable.

“You know, if I was a happy, jolly guy when I was fighting, we wouldn’t be having this interview,” he laughs. “I had to be that guy for that job. For this job, I don’t have to be that guy. That guy back then would have never been able to do this, he wouldn’t have had the desire to do it.”

If those two versions of himself ever met, what words of wisdom would he pass on to his younger self? “I would tell him that in the end you’re going to be OK,” he says. “You’re going to go through ups and downs in life, that’s what life is. But at the end of the day you’re going to be OK.”

As Tyson discusses his life, the conversation is never too far from veering into the philosophical. Just as the veneer of intimidation melts away through discussion, so too does any misconception that Tyson’s lack of formal education means he’s anything less than a deep thinker. He is incredibly well-read, namechecking Richard Wright, Carl Jung and Mark Manson within minutes of each other.

Tyson is a seeker. He wants to experience and understand as much of this world as he can in the short time he is here. When he was serving just under three years in prison, there wasn’t much for him to do besides read. It was during that time that he picked up a book sent to him by director Spike Lee—“Days of Grace” by Arthur Ashe.

“Spike gave me the book and went through the book and what a thing,” he says. “I flew through it, then read it again. I felt a kinship to [Ashe]. He was very intelligent and he held back that intelligence, he was just nonconfrontational. I respect that. I wish I could be nonconfrontational but it just wasn’t meant to be. I felt a kinship there, so I put a tattoo there.”

At the time there was no way he could have known how strong a presence Ashe would be in his life. Years down the road he would meet his wife Kiki and learn that Ashe gave her a tennis racket when she was a child. And today their daughter is an outstanding tennis player. “How is that possible?” Tyson muses. “I have the tattoo on my arm, my wife has a racket from him, and our daughter plays tennis. It’s crazy.”

Tyson loves to ponder connections like that as he tries to find the answers to the unanswerable questions. And even if he doesn’t find the answers, he’s going to keep on trying. “Knowledge is infinite,” he says with a mischievous grin. “Just think about it, why the fuck were we born? No, why were we born being afraid to die? [Before I was born] I was blacked out, didn’t matter where the hell I was, but I was cool, now I’m here and now I’m scared to die. Tell me about that. I don’t know if I’m scared of death, but I’m not clinging to life.

“Life is suffering,” he continues. “It’s all about handling suffering and adversity, not giving into it, seeing how tough you really are. Life is a fight, the world is a never-ending place of disappointment. It’s all conflict, even if it’s just conflict within yourself.”

Learning to deal with one’s internal demons and conflict from within is one of the greater challenges a person can take on. The stigma that unfortunately still surrounds many aspects of mental health can make the challenge even more difficult. In his personal journey toward wellness Tyson found an ally—cannabis.

“It helps me. If I don’t smoke my wife and kids can see a big difference,” he explains. “It just changed the channels and my thoughts from being a dick to being a respectable guy, being nice to the kids and nice to the wife.”

It was in this spirit that Tyson 2.0, his cannabis brand, was born. A lot of celebrities get into the cannabis space in order to have their own strain and look cool, but Tyson was inspired by the personal growth he had experienced using cannabis. Is he an entrepreneur marketing a successful business with Tyson 2.0? Without a doubt. But money or clout is not the driving force behind the venture.

“I really think I can help people,” he explains. “I want cannabis to have a different kind of image. I don’t want to hear, ‘Hey, I want a drug.’ Cannabis is not a drug, it’s a medicine. That’s what it is.”

That being said, Tyson 2.0 is a business in a market that has suddenly become flooded as attitudes, and laws, toward cannabis use change. In a brilliant stroke of marketing they came up with the Mike Bites—edibles in the shape of an ear with a bite out of it. While Evander Holyfield might not be so enthused, customers have been.

“I can’t handle them,” Tyson laughs. “I’m just not programmed to handle the gummies yet. I don’t want to take this stuff and then go into a meeting and start crying. I can’t believe in a billion years that I’m talking to you about this stuff. I’m a neophyte in this business, I can’t believe we’re doing this and that the country has made it legal in most of the states. I’m glad I got involved.”

As we talk, Tyson is always quick to acknowledge the people who have helped him build Tyson 2.0 and the rest of his business ventures. It’s clear that he loves his team and that his team returns the same adoration. As they explore new opportunities, his team isn’t going to be pushing him to do things just to make a quick buck; everything he’s involved with makes sense. For example, Tyson is an outspoken advocate for holistic medicine, hence the line of nootropic supplements he collaborated with Jones Soda to produce. Money, while nice, is never the end-all-be-all of these endeavors.

One can speculate where this attitude originated within Tyson. It may have stemmed from the teachings of his late trainer, Cus D’Amato. “He was pretty socialist…” But more likely it comes from the life experience he has had, particularly when he was fighting addiction.

During his years as a self-proclaimed “relapse artist,” Tyson befriended, and got high with, many fellow addicts. They would go to rehab and then spend the summer partying before returning to do it all again.

“We’d go to Greece or the south of France and hang out, then we’d go to rehab and we understood why we were all there,” he says. “Most of my friends passed away. That’s what happens. My wife had to deal with me through my relapses, my ODs, my heart busting. It was the birth of my daughter that made me say, ‘I gotta stop. We gotta make this work.’ She kept us together, she was the glue.

“My friends had all the money in the world, all the money in the world,” he continues, “and it couldn’t stop them from killing themselves. I’m just grateful I learned the power of gratitude.”

Listening to him talk about life, plenty of intriguing dualities within Tyson’s psyche are revealed. One of the most fascinating is the role fame has played in not just his life, but his journey of self-discovery.

Hidden in a joke he makes about thinking he’s a bit overrated as a boxer, it’s clear that issues of self-esteem have plagued Tyson throughout his life. To many it seems impossible that the boxer who once won 37 consecutive fights, 33 by knockout, would have any moments of self-doubt.

Whenever Tyson goes in public people recognize him and come up to him, and it isn’t a minor annoyance of fame that he brushes aside. Instead it unleashes some of his darker thoughts about himself.

“Nobody is that great where people [need to] stop them in the airport,” Tyson explains. “It’s cool, but it’s creepy. I might not be that bright, but I’m deeper than that. It makes me very uncomfortable.”

As those people idolize Tyson the boxer, we want to know what Tyson the man would want them to know about himself.

“I want them to know I have low self-esteem,” he says. “I don’t even know what you call it, an annihilation of fucking ego, what do you call that person? The kind of person that has a low self-esteem but has everything, and everybody loves him? Why did God make me this person with this low self-esteem and allow me to have all this?”

Tyson has a very complicated relationship with the concept of ego. In those moments of self-doubt he seems to have none, but when he was on the mic promoting a fight he appeared to be nothing but ego. The reality is somewhere in the middle. Tyson learned the key to controlling his own ego when he looked deeply within himself while on psychedelics.

“I’ve done this serum they call the toad, when I first did it I thought I was dying, I was so scared,” he explains. “My ego died, and you’d be surprised how much we need that. People say throw your ego away, kill your ego… no. That’s all bullshit. If the ego dies, we die. Don’t let it control you. The ego’s purpose is to protect you. We’re so much more than what we think we are, we just don’t know what it is.”

That statement was intended to be addressing the big picture, the possibilities of the human mind, but Tyson has proven throughout his life that it is equally true of himself. The public perception of Mike Tyson has been constantly in flux.

As Public Enemy blasted out the speakers and shook all of Las Vegas when he walked out to the ring to fight Razor Ruddock, there was no denying the perception that Tyson was the baddest motherfucker on the planet. As he dropped Zach Galifinakis to the tunes of Phil Collins with the best choreographed punch in the history of Hollywood, the perception was that of an entertainer willing to have a laugh at himself. And as we sit in his living room discussing Che Guevara, his cannabis venture and Carl Jung, the perception is of a deep thinker intent on healing himself and hoping to heal others along the way.

Over the course of an hour, our conversation veered in a variety of unexpected directions, which was the one expected outcome I had walking in. And while we had spent some time discussing Tyson’s tattoos and how they reveal truths about his story, we hadn’t yet brought up tattoos other people get of him.

“What is it like when you see your face on another person’s skin?”

Thirty seconds pass as he silently gives the question thought.

“I have great respect for their perception of me without even knowing me.”

“Do you wish they understood who you really were as opposed to just the perception?”

“Some days I have really low self-esteem and when I see tattoos on people, making me more than I think I am, I don’t feel good,” he explains. “I don’t know why God made me this way. I should really absorb this stuff… maybe I feel like I don’t deserve it.”

“I think those people are doing it because they’re trying to identify with that ferocity from your career and they find it inspiring.”

“But they never knew that I was afraid,” he says. “If they knew I was afraid I would respect that tattoo. But they don’t know that, they think I’m an animal. They can’t wait to see me beat somebody again. That’s how the tickets were sold, the great fighter had to be a great entertainer and make the people feel in awe.”

It’s a hard thing to hear him say. People know he was afraid—fear is the most relatable of all emotions, most of us are scared multiple times every single day. Tyson is just one of the few willing to admit it. It’s not Tyson’s ferocity that inspires people; it’s his unabashed humanity.

Mike Tyson certainly doesn’t have all the answers, but he does possess a wealth of wisdom, as well as curiosity, empathy, intelligence and humor. He’s a man trying to do his best for himself, his loved ones and others, grateful for the opportunity to wake up each morning. That’s the perception people have of Mike Tyson in 2022. Perhaps someday he’ll see it in himself.

Creative Agency/Production: Early Morning Riot

DP: Justin Carter

Lighting Tech: Ram Gibson

Lighting Assistant: Lynwood Robinson

Photo Assistant: Cam Lindfors

Groomer: Troy Jensen

Barber: Dante Minners “Breeze”

Stylist: Jay Hines/The Only Agency

Stylist Assistants: Cameron Garcia, Carl Lovestrand, Gabriella Lane

Prop Stylist: Danielle Ponce

Location: Four Seasons Hotel, Beverly Hills